Qivalis and the Dawn of Bank-Led Tokenization in Europe

This is a follow-up to our article from September 2005: Europe's Push for Digital Sovereignty: The Launch of a MiCAR-Compliant Euro Stablecoin by Nine Major Banks

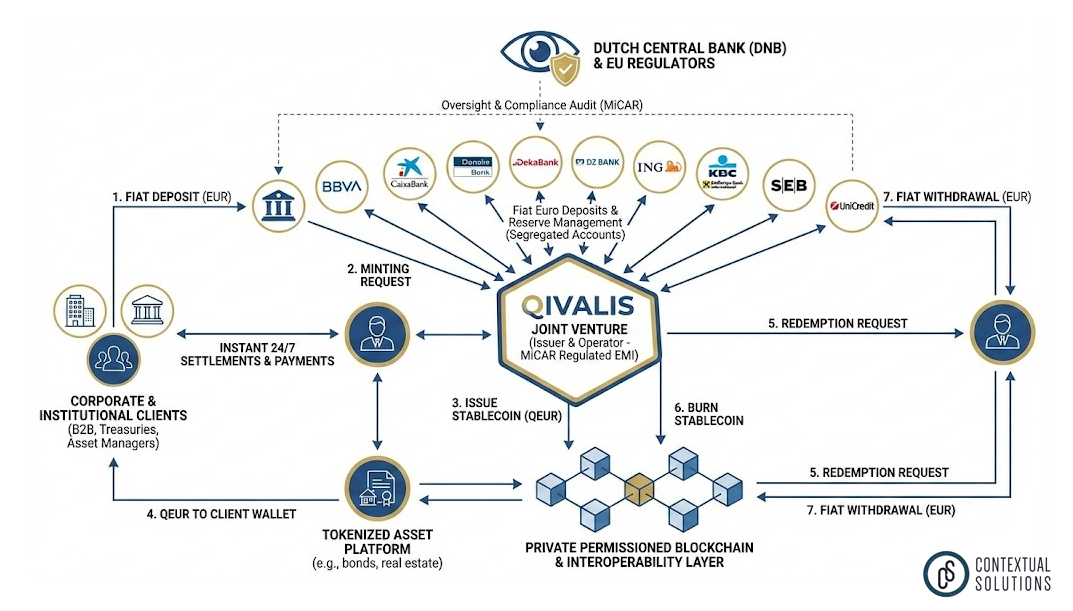

The week of February 4, 2026, marks a watershed moment in the history of European finance. With the official entry of BBVA into the consortium, the formation of Qivalis is now complete; a joint venture comprising nearly a dozen of Europe’s most powerful banking institutions. This alliance, which includes heavyweights such as BNP Paribas, ING, UniCredit, and the newly added Spanish giant BBVA, represents the traditional banking sector’s most ambitious answer to the digital asset revolution. Their goal is clear: to launch a fully regulated, euro-pegged stablecoin by the second half of 2026.

For years, the stablecoin market has been the domain of crypto-native entities like Tether and Circle, often operating in regulatory gray zones or offshore jurisdictions. Qivalis signals a definitive end to that era in Europe. By leveraging the European Union’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCAR) framework, these banks are not merely dipping their toes into blockchain technology; they are building a sovereign, institutional-grade payment rail designed to reclaim control over digital settlements. This essay explores the strategic rationale behind Qivalis, its operational framework under MiCAR, the potential disruption to legacy payment systems, and the broader implications for the global financial order.

Why Qivalis?

The formation of Qivalis is driven by a convergence of defensive and offensive strategies. Defensively, European banks have watched with growing unease as U.S. dollar-denominated stablecoins (like USDT and USDC) captured the lion’s share of the digital asset market. This "dollarization" of the crypto economy posed a threat to the euro’s sovereignty in the digital age. If the future of finance is on-chain, and 99% of on-chain liquidity is in dollars, the euro risks becoming irrelevant in the emerging Web3 economy. Qivalis is, in many ways, a geopolitical maneuver—a "sovereign" counterweight designed to ensure that euro settlement remains a viable option for digital assets.

Offensively, the banks recognize that blockchain technology offers efficiency gains that legacy rails cannot match. Traditional cross-border payments, relying on the correspondent banking network (Swift), are often slow, expensive, and opaque, plagued by cut-off times and reconciliation delays. A blockchain-based stablecoin allows for 24/7, near-instant settlement. For the banks involved—spanning from the Nordics (Danske, SEB) to the Mediterranean (CaixaBank, BBVA, UniCredit) and the DACH region (DZ BANK, Raiffeisen)—a shared stablecoin infrastructure allows them to settle payments between themselves and their clients without intermediaries, effectively creating a private, highly efficient clearing network that is interoperable with the broader blockchain ecosystem.

MiCAR as a Catalyst

The timing of Qivalis is inextricably linked to the full implementation of the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR). Prior to MiCAR, banks were hesitant to engage with stablecoins due to reputational risks and regulatory uncertainty. MiCAR has changed the calculus by providing a clear rulebook. It establishes strict requirements for reserve backing, redemption rights, and governance, effectively creating a "regulatory moat" that favors well-capitalized institutions over agile but riskier startups.

Qivalis is seeking authorization as an Electronic Money Institution (EMI) under the supervision of the Dutch Central Bank (DNB). This choice of jurisdiction is strategic; the Netherlands is known for its rigorous but innovation-friendly financial oversight. By operating as a fully regulated EMI, Qivalis can offer a level of trust that crypto-native issuers struggle to match. For institutional clients—pension funds, asset managers, and corporate treasuries—regulatory compliance is non-negotiable. Qivalis offers them a digital cash equivalent that bears the seal of approval of Europe’s top regulators, mitigating the counterparty risks that were highlighted by the collapse of algorithmic stablecoins and offshore exchanges in the early 2020s.

Operational Mechanics and Use Cases

While the retail crypto market often focuses on speculation, Qivalis is squarely aimed at the wholesale and B2B sectors. The initial rollout in late 2026 is expected to focus on three primary use cases:

One of the most touted benefits of Qivalis is "programmability." Unlike standard bank transfers, a stablecoin can be embedded into smart contracts. This allows for conditional payments—for example, a supply chain smart contract that automatically releases payment to a supplier only when a digital bill of lading is received and verified. For industrial giants in Germany and France (clients of DZ BANK and BNP Paribas), this automation could unlock billions in working capital efficiency.

Multinational corporations often hold fragmented pools of liquidity across different banking partners and jurisdictions. A standardized euro stablecoin would allow these firms to move liquidity instantly between subsidiaries and banks without waiting for T+2 settlement cycles or paying high FX fees. This "cash on chain" model enables real-time liquidity management, a holy grail for corporate treasurers.

As banks increasingly tokenize real-world assets (bonds, commercial paper, real estate), they need a cash leg for the transaction that lives on the same ledger. Currently, settling a tokenized bond purchase often requires moving the asset on-chain while the cash moves off-chain via Swift, reintroducing delay and risk. Qivalis solves the "Delivery vs. Payment" (DvP) problem by allowing both the asset and the cash to swap simultaneously on the blockchain, eliminating settlement risk.

Banks vs. Crypto-Natives

The launch of Qivalis sets up a fascinating clash of cultures and business models. On one side are the crypto-natives like Circle (issuer of EURC) and Tether (EURT). These companies have the advantage of "open loop" systems; their tokens are already integrated into thousands of DeFi protocols, exchanges, and wallets. They prioritize speed, permissionless innovation, and global reach.

On the other side is Qivalis. Its competitive advantage is distribution and integration. The 11+ banks in the consortium serve over 150 million customers collectively. If they integrate Qivalis wallets directly into their existing mobile banking apps and corporate portals, they can achieve immediate mass adoption without requiring users to navigate complex crypto wallets or seed phrases. Furthermore, banks can incentivize adoption by offering lower transaction fees for internal settlements or by making the stablecoin the default settlement instrument for their tokenized asset platforms.

However, Qivalis faces a significant challenge: the tension between "walled gardens" and the open internet. If Qivalis is only usable within the private permissioned networks of the member banks, it will fail to capture the liquidity of the broader Web3 economy. The success of the venture will depend on its interoperability—whether it can be safely bridged to public blockchains like Ethereum or Solana where the actual digital asset activity is happening, or if it remains trapped in a banking consortium intranet.

Challenges and Risks

Despite the optimism, the road to H2 2026 is fraught with hurdles. Governance is the most obvious challenge. Consortia in the banking sector have a mixed track record (e.g., the slow progress of the European Payments Initiative). aligning the interests of 11 fierce competitors—who fight daily for the same corporate clients—will require deft diplomacy. Decisions on fee structures, revenue sharing, and technical standards could bog down progress.

Technologically, the project must navigate the "trilemma" of privacy, compliance, and transparency. Public blockchains are transparent by default, but bank clients require strict financial privacy (GDPR and banking secrecy). Qivalis will likely utilize Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) technology or private subnets to obscure transaction details while proving validity to regulators. Getting this architecture right is complex and untested at this scale.

Finally, there is the risk of adoption inertia. Corporate treasurers are conservative. Moving from a familiar (albeit slow) Swift transfer to a blockchain-based token involves new operational risks, tax implications, and accounting treatments. The banks will need to invest heavily in education and user experience to convince their clients that the switch is worth the effort.

Conclusion

The formation of Qivalis is more than just a product launch. It signals that European banks are no longer content to watch the digital asset space from the sidelines. By combining their regulatory privilege, vast capital, and customer reach, they aim to domesticate the stablecoin innovation—stripping away the "wild west" elements and repackaging it as a boring, reliable, and essential piece of financial infrastructure.

If successful, Qivalis could become the backbone of a new European financial internet, reducing reliance on American payment rails and fostering a truly digital single market. However, if the consortium succumbs to internal bureaucracy or fails to build a product that is genuinely interoperable with the open crypto economy, it risks becoming a digital "white elephant" — impressive in theory, but ignored by the market. As the H2 2026 launch approaches, the eyes of the global fintech community will be fixed on Amsterdam, waiting to see if the giants of Old Finance can truly learn to dance to the rhythm of the blockchain.