Operation Chargeback: Unmasking €300 Million in Fintech Fraud

(source: BKA)

In November 2025, a coordinated international law enforcement effort, "Operation Chargeback," dismantled a sophisticated financial fraud network that had siphoned an estimated EUR 300 million from 4.3 million credit card holders across 193 countries. The operation, the result of a nearly five-year investigation, uncovered a scheme staggering in its global scale and subtlety.

“Operation Chargeback is a testament to the power of international cooperation in dismantling complex criminal networks. It underscores the critical role Europol plays in supporting law enforcement agencies across the globe. By leveraging our analytical capabilities and facilitating cross-border coordination, we have been able to bring down the networks defrauding millions of credit card users worldwide.”

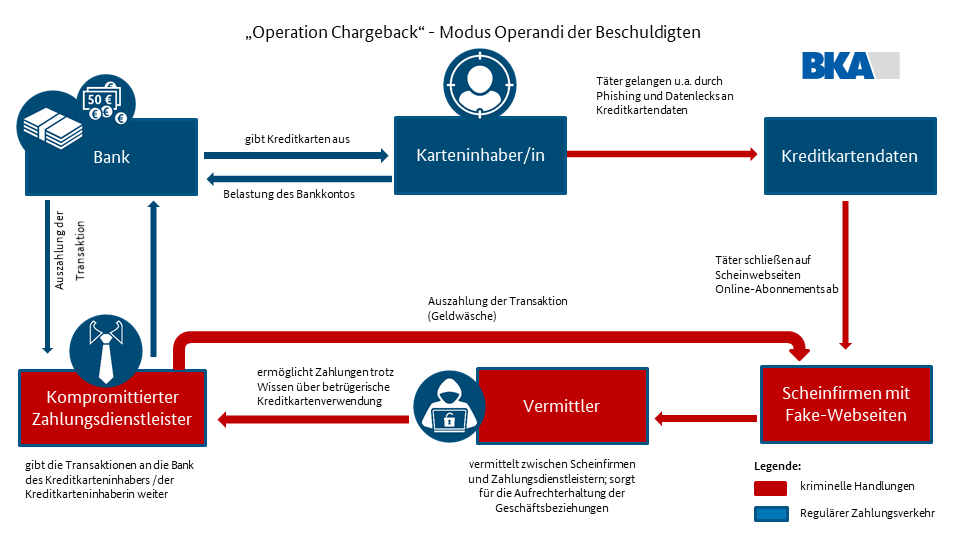

Operating between 2016 and 2021, the three criminal networks did not engage in high-value theft, which triggers immediate alerts. Instead, they employed a "low and slow" modus operandi designed to operate beneath the radar of standard fraud detection. The perpetrators used stolen credit card data to create approximately 19 million fraudulent online subscriptions to services hosted on "professionally operated websites," primarily offering adult content, dating, and streaming. These sites were "deliberately hidden from search engines," rendering them invisible to automated security crawlers and victims.

The scheme's brilliance lay in its payment structure. The networks processed "small, recurring payments" of approximately EUR 50 ($57) per month; an amount high enough to be profitable at scale but low enough to be overlooked by consumers scanning their statements. Vague billing descriptions compounded the problem, making charges unidentifiable.

The operation's name refers to its core design: the neutralization of the chargeback system, the primary consumer protection mechanism for disputing fraudulent charges. When a victim did notice and dispute a charge, they found the transaction was processed by one of "numerous shell companies". By the time an investigation began, the shell company was often defunct and its accounts emptied, the funds already laundered through a complex network involving over 2,000 German bank accounts. As Eurojust noted, this structure "made it very difficult for victims to charge back the fraudulent payments".

“With the successful investigations to identify the criminal networks and the resulting arrests, German and international authorities have dealt a significant blow to the global financial fraud scene. The proceedings illustrate the increasingly complex structures of cross-border economic crime, but also the capabilities of the investigating authorities and their partners.”

- Martina Link, Vice President of the Federal Criminal Police Office

Complicit Insiders and the CaaS Ecosystem

A fraud of this magnitude could not have been executed by external actors alone. Its success was contingent on active, high-level collusion from within the legitimate financial system. The investigation revealed that the suspects "exploited the infrastructure of four major German payment service providers" (PSPs) to process and launder the EUR 300 million.

This was not mere negligence. Among the 44 suspects targeted and 18 arrested were "executives, compliance officers and risk managers" from these same payment firms. According to investigators, six of these individuals allegedly "colluded with the fraud networks" to grant them access to the financial infrastructure "in exchange for fees". This represents a terrifying inversion of the "three lines of defense" model, where the very individuals tasked with preventing financial crime allegedly became its paid enablers.

The complicity was also technological. One German PSP is accused of having "developed customized software" for the criminal networks that "allowed for the movement of funds through virtual accounts, masking the source of transfers". This was not RegTech (Regulatory Technology); it was "Crimetech" developed to facilitate and obscure mass-scale laundering.

This internal collusion was supported by an external "Crime-as-a-Service" (CaaS) supply chain. CaaS providers supplied the "thousands of shell companies" used to process payments, "primarily registered in the U.K. and Cyprus"; jurisdictions chosen for their ease of company formation. These vendors provided "full corporate packages," including "fake directors" and "forged know your customer (KYC) documents," creating a vast, disposable, and seemingly legitimate network for the criminals.

The Specter of Wirecard

The "action day" on November 4, 2025, was a testament to international cooperation. Led by German authorities (the Koblenz General Prosecutor's Office and the BKA) and supported by Europol and Eurojust, the takedown involved raids and arrests across nine countries, including Germany, the US, Canada, and Singapore.1 The complexity was immense, with investigators filing over 90 legal assistance requests with 30 different countries.

“Recent events show how drastically the commission of property crimes has changed due to the use of digital tools and how extensive the resulting damage can be. It is therefore good that such crimes can also be curbed through the intensive and coordinated efforts of the authorities.”

However, the investigation's timeline and context reveal a far more disturbing story. The Operation Chargeback investigation did not occur in a vacuum; it unfolded against the backdrop of the 2020 collapse of Wirecard, the largest financial fraud in post-war German history.

In a stunning development, German prosecutors from the Koblenz Public Prosecutor’s Officet (the same agency leading the Chargeback investigation) revealed that they "suspect former Wirecard executives, including fugitive ex-Asia head Jan Marsalek, of helping run the very fraud network dismantled in Operation Chargeback.

This allegation recasts the entire narrative. The timelines are a perfect match: the Chargeback fraud ran from 2016 to 2021, the exact period of Wirecard's most egregious fraudulent operations and Marsalek's influence, which culminated in its 2020 insolvency. This suggests the German fintech sector was not facing two separate scandals, but a single, systemic "German PSP Crisis." The Wirecard scandal was not an anomaly but merely the "flagship" operation of a wider penetration of the German financial sector by criminal networks, allegedly linked to Marsalek, who is also suspected of being a Russian agent.

A Failure of National Supervision

At the center of this systemic crisis is Germany's Federal Financial Supervisory Authority, BaFin. BaFin's role in Operation Chargeback is a study in contradiction. In 2025, BaFin was an active participant in the raids, and its head, Birgit Rodolphe, stated that the fraud was "completely stopped since 2021" precisely because of pressure from BaFin.

This, however, was a deeply reactive measure. The fraud ran unchecked for five years (2016-2021) directly under BaFin's supervision. This was the same period during which BaFin was failing in its supervision of Wirecard. Academic analysis of the Wirecard failure found BaFin was compromised by a "home-country bias," institutionally incentivized to protect its "national economic champions" from "allegations coming 'from abroad'". Famously, BaFin banned the short-selling of Wirecard shares and filed criminal complaints against the Financial Times journalists who were reporting the truth.

This "home-country bias" created the exact supervisory blind spot that the Chargeback networks exploited. While BaFin was busy protecting its "national champion" Wirecard, a criminal network (allegedly linked to the same Wirecard executive) was able to compromise and corrupt four other German PSPs for five years.

The 2020 Wirecard collapse left BaFin globally discredited. Under new leadership, the agency was forced to confront its failure. In a candid 2025 interview, new BaFin President Mark Branson delivered a stunning mea culpa, stating: "We are talking today with the benefit of hindsight... broadly speaking, your institution got it right; ours got it wrong."

The Imperative for European Resilience

Operation Chargeback, when viewed alongside Wirecard, is a "textbook example of the structural shortcomings of nationally organised supervision" in a borderless single market. The "home-country bias" that incentivizes a national regulator to protect its domestic firms is not a personnel flaw but a structural one.

In response to Wirecard, Germany passed the Act to Strengthen Financial Market Integrity (FISG) to give BaFin "mehr Biss" (more bite). This law strengthened BaFin's powers and imposed stricter rules on corporate governance and internal controls. But this is a national solution to a European problem. It does not solve the fundamental "home-country bias" or the inability to supervise complex, cross-border criminal enterprises.

The evidence from Operation Chargeback provides a powerful mandate for a centralized, pan-European regulatory framework. This scandal is the single strongest argument for the new EU Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA). A supranational body like AMLA would have direct supervisory power over high-risk, cross-border entities, like the PSPs implicated in this fraud. It would have no "home-country bias" and the holistic view necessary to connect German PSPs, UK/Cyprus-based shell companies, and forged KYC documents. This case also proves the urgency of the EU's 6th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD) to shut down the CaaS "shell company" supply chain and new frameworks like the EU Cyber Resilience Act to combat the development of "Crimetech".

For the European financial services community, the implications are profound.

For Fintechs: The arrest of "executives, compliance officers and risk managers" 7 is a paradigm shift. The risk has evolved from corporate fines to personal, criminal liability. Investment in robust RegTech and a genuine culture of compliance is now a matter of existential survival.

For Banks and FIs: The trust model for bank-fintech partnerships is broken. The "three lines of defense" at a fintech partner cannot be assumed to be functional; as Operation Chargeback shows, they may be actively complicit. Banks must now operate under a "zero-trust" model, conducting intrusive and continuous due diligence on their PSP partners.

For Investors: The C-suite and compliance-level collusion, combined with the total fabrication of Wirecard's business, fundamentally rewrites the due diligence process. The integrity of a fintech's compliance culture is no longer a "soft" metric; it is the primary indicator of catastrophic, balance-sheet-wiping risk.